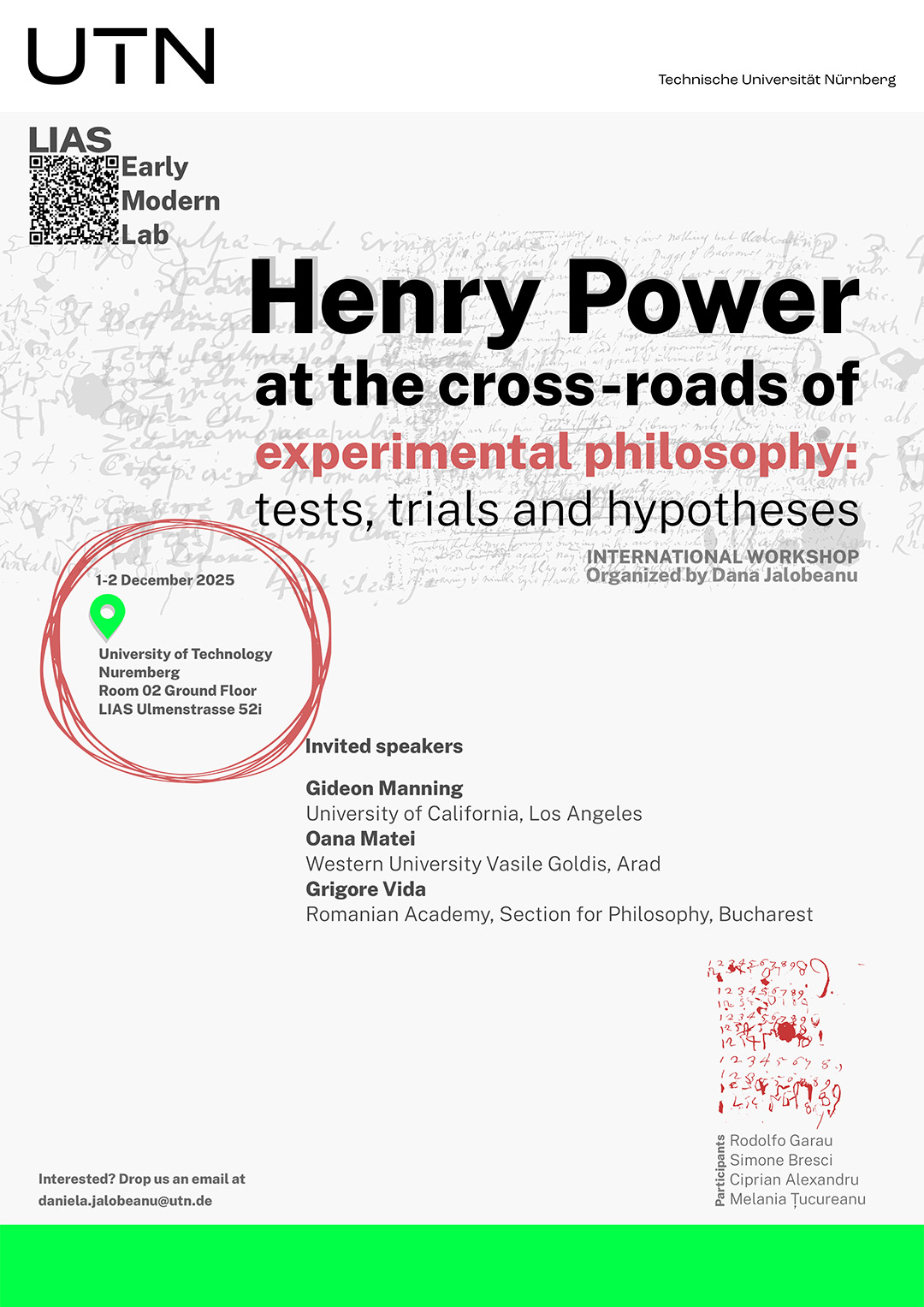

Workshop organized by Dana Jalobeanu

1-2 December 2025, University of Technology, Nuremberg

Invited speakers: Gideon Manning (Claremont Graduate University), Oana Matei (Western University Vasile Goldis, Arad), Grigore Vida (Institute of Philosophy of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest)

Henry Power is one of the underappreciated figures of the Scientific Revolution. His only published book, Experimental philosophy, (London, 1664) was often cited, widely owned, but rarely discussed; and it has never benefited from a modern edition. The secondary literature casts him as a marginal figure in the emergence of early modern science; someone who died too soon, before his ideas had entered the intellectual arena of the mid-seventeenth century. And yet, many agree that Power’s life and work, and the networks in which he participated, tell us a great deal about shifting intellectual and practical alliances and the ferment of knowledge. Indeed, several of the most important experimental projects of the seventeenth century can be traced back to Power. He was, for example, the first to discover the law of gasses (i.e., Boyle’s law, or Boyle-Mariotte’s law); an early systematic microscopist; actively engaged in the experimental program that aimed to detect variations of gravity; and his work on magnetism, generation, and the sensitivity of plants left recognizable traces in later seventeenth-century debates. Most recently, scholars have focused on Power’s humanist methods of reading, writing and commonplacing, drawing attention to his large archive.

This conference aims to study the complexity of Henry Power’s Experimental Philosophy, its genre, its structure, and its sources. What keeps together Power’s investigations into spontaneous generation, pneumatics, magnetism and gravitation? How did he develop his ideas and draft his work? What is ‘philosophical’ about the Experimental philosophy? How was his work received, and what does that reception tell us about the different sects of natural science at the time?

More specifically, presenters might consider how to understand the curious mixture of Baconianism and Cartesianism so characteristic of the Experimental philosophy? What were the sources of Power’s particular form of atomism? What was the intellectual background (and questions) of his discussions on ‘spirits’ and his beliefs that living beings function as a sort of ‘distillatories’? Is there really a conflict, in Power’s works, between Cartesianism and Neoplatonism or do we need to take into consideration other sources and influences? What counts as ‘observations’ in the Experimental philosophy? What kind of experimental techniques are used in the book? What conventions of representation are adopted; more generally, why are Power’s microscopical experiments so different than Hooke’s, which were published just one year later? What precisely are experiments ‘doing’ in the construction of his ‘experimental philosophy’?